Barry Can't Swim

Barry Can't Swim

why

From our experience one of the hardest steps an artist takes is in the build up to their first sold out academy level shows. They have spent the years prior to this developing their sound and performance on an extremely tight budget. Suddenly they have an enormous stage to fill and an expectation to level up the performance.

Almost immediately the creative team around the artist grows, along with the budgets – and a feeling of vertigo is not uncommon. We have been through this process with multiple artists and have come to realise that collaborating with them at this point in their careers on a holistic level is equally as important as on a creative level.

Barry Can’t Swim’s growth over 2024 was meteoric. We had been already working with Josh and his team for some time, helping to sculpt their first album campaign. but no one could anticipate at that time we would be creating three sold out Brixton Academy shows at the end of the year. When approaching shows like this one of the first questions we ask ourselves is what elements from the previous work with the artist are worth retaining, and where do we want to start fresh. The visual language of an act is something that grows over time, often being reinvented entirely multiple times over their career.

After researching and spending time with Josh, it became abundantly clear how important the act of performance is as part of his identity. He is an immensely musical person, having spent a large amount of time playing instruments from a very young age. Whilst his compositions are undoubtedly routed within dance culture, demonstrating his musicality would clearly be the most genuine way of presenting him on stage. This would have to be balanced with the understanding that this still had to remain a show that was experienced, not watched.

what

Our research, as it usually does, took us down many divergent paths. Quickly it became clear that by treating it as an electronic music show felt like a square peg in a round hole.

We needed to retain the energy and togetherness of a rave, but integrate elements which spoke to the virtuosity and abundant joy of watching a live band on stage. This led us down the route of something with its roots in theatre. We were interested in the fluidity by which theatrical productions can change the state and shape of the stage, shifting the audience’s perception of location. There was something in Josh’s music that felt intrinsically durational, so if we could find a way to physically define ‘Acts’ of the show, we could visually accompany what the musical team were planning with the set list.

Several of our original sketches involved a fairly elaborate set design, where we looked at splitting the stage up into different performance areas that would be used individually during the show. The stage itself would represent a living room, that would slowly evolve during the performance, with objects that at first just seemed like they were part of the background eventually revealing themselves to be a bigger part of the performance, as if the house itself was alive. Lighting and LED screens would be concealed in the set, providing an effect without the audience being able to see the source of the light, which might break the illusion – a method that formed part of the Gesamtkunstwerk movement that became prevalent in opera and theatrical design.

Alongside this concept, we worked on something that felt like it embodied the same theory, but based on a very different ideology. It’s fairly common during a design process for us to ask ‘what would happen if we rebelled against the ideals we have created?’ Sometimes you have to make a rule to break a rule.

What would happen if we removed everything from the stage altogether, but still retained the theatrical underpinnings?

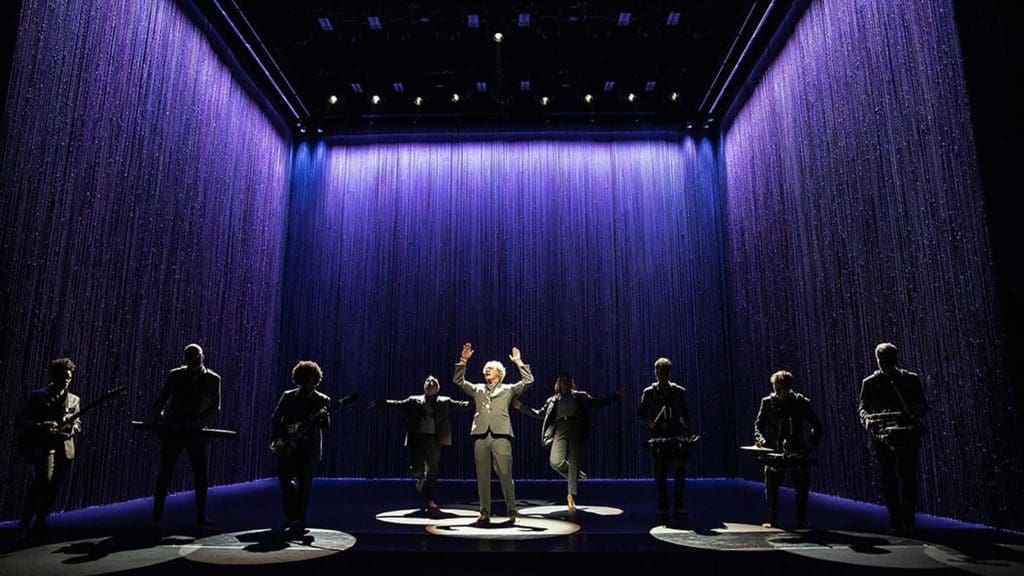

We looked productions such as David Byrne’s American Utopia – a Broadway show, but with musical performance at its core. Keeping the stage as a simple box design gave each of the musicians space to make the stage their canvas – the element of performance became the showcase. We started working up a design based on these principles.

A simple ‘open box stage’ was created, we then started to consider what elements we would use to create it.

As the visuals had already become an important element in the language of the show, we wanted to adapt this into this new production.

The rear of our box would become a vast LED screen – as big as we could fit inside the venue. Completing our open box design, we used the same lighting fixture for the walls and overhead. Picking the right light for a production always comes down to multiple factors – this is especially important when the light has to perform a dual role of being both flexibly functional as well as its presence being a visible architectural element.

The result can be seen as a re-imagining of the stage into something more bespoke – a space within a space.

Even this design concept went through multiple iterations and rounds of feedback, both internally and with the artist and production teams. The original version had all 3 sides of the box constructed from LED screen – it was only later we decided to construct the side walls out of lighting fixtures to even the spread of elements across the design, and to allow more complex lighting looks across the structure.

However there was still an element that was missing. Along with the musicians, we wanted the production itself to feel kinetic and alive, as if the lights themselves were also performing. This way we could transform our blank canvas stage entirely – creating smaller moments of intimacy during softer tracks in which Josh typically performs solo – alongside vast expansions of space and scale at other times.

To achieve this we designed the overhead lighting trusses to be rigged so that they could move individually during the performance. This gave us the freedom to dramatically change the stage, allowing us to script a physical narrative arc for the performance.

To add a final theatrical flourish, we added some spotlights that would be lowered and raised individually on winches. Whereas the moving trusses added this kinetic feeling of scale, these spotlights would move in a way that felt smaller and more delicate and would help highlight Josh in certain moments of the show.

Working closely with the band, alongside Music Director Mike Lesirge was pivotal. When considering a show with so many literal moving parts – choreographing the connection between performer and technology becomes a delicate and constantly evolving situation. The aim of any production is to try and empower or protect an artist, depending on what they need to feel comfortable. It was incredibly important to find a way of staying flexible to changes that would come out of the rehearsals as the band worked on the performance.

‘Mike says something about how working together made the show better.’

how

Whilst the musicians were locked in rehearsals, our creative and production teams were engaged in the business of producing the show.

Programming a show like this involves bringing together all the different visual elements that make it up and working to sculpt them into an overall vision that feels inherently connected. For this show this included Lighting, Visuals and Lasers. We’ve found the best approach for this is to allow each department the space to collaborate but also to go off and explore tangents on their own in equal measure.

Our philosophy for this is a two fold approach. Firstly – throwing as much paint on the wall as we can, to see which paths are worth following. Secondly – scraping away large quantities of it until we’re left with something that can tell a story without indulging in itself.

For the visuals, the hand animated style gave the show a very distinctive look – once we committed to this it felt very important that we stayed in this world all the way through the show. Half the problem with a show like this is keeping the audience committed to the world you are creating for them. It’s so easy for people to get jolted out and back into reality. So once you have set the scene, any change in visual style would be uncomfortable. This provided us with several issues, as when animating in this particular style it is very difficult to create fidelity – every element is bold. This is exacerbated by the scale and high contrast brightness of the LED screen. We also felt it was really important that, whilst it was of course important that visuals were beautiful and engaging, they did not dominate the stage. The focus must remain primarily on the musicians and connection between them and the production. To achieve this, you sometimes need to think of the screen as just another light, albeit a very large one. Considering it in this way, the images can become something that is almost visually onomatopoeic, with elements on screen representing individual sounds. Good examples of this can be found all through the history of visual art, more recently in a lot of Michel Gondry’s work, such as the video for Chemical Brothers Star Guitar to much earlier experiments like Oskar Fischinger’s Komposition in Blau from 1935, which is seen by many as the genesis of what would become the modern music video.

Other times, we found we could use this screen simply as a way of highlighting the band members or the stage design – using block colours and gradients as a way of creating iconic moments that integrate the LED screen with the other elements of the show.

Jake

What is your process when for programming a show like Barry Can’t Swim?

I listen to the songs a lot beforehand to get a feel for how the show is going to look and where the moments are going to be. I mark all of the tracks so I any specific cues I want and are logged, and then import all of that into the desk. I like to do a lot of prep on my showfile so that everything is in the same place as I’m used to – this just makes the process of programming the show a lot quicker and easier as all my macros and plugins are where I need them.

When I’m programming I try not to make too many notes or edits in previz. I like to do a couple of runs and then leave it as it is because I find a lot of the best ideas come when you’ve got a full rig in front of you – and it never looks the same anyway!

Were there any influences in your programming style from other shows?

Yeah. I spend a lot of time on YouTube looking at other people’s shows. In my opinion, some of the best programmed shows are Taylor Swift, the Jonas Brothers, Stormzy, which is programmed by James Scott, so I try and look towards those for inspiration. I really love the Justice show and how simple and clean it looks with everything being on or off. And also the David Byrne show on Broadway, which is lit by Rob Sinclair is amazing to watch – again because of how simple it is with the shadows on the drape.

How much did the moving lighting elements of the show influence what you programmed, and how did you adapt to this?

I actually did all of the kinesis moves first and then programmed the lighting to it. I feel this was much better because I could tailor the lighting programming to what the stage looked like, rather than the other way round – I don’t think you’d get the best results doing it that way. For example, when the trusses were all at 45 degrees, because I knew the position of the truss, I realised we could run a slow dimmer chase down it to look like water falling – so for moments like that, I think it’s much better to do the positions first, figure out what the stage looks like, and then you’re not overthinking the lighting programming.

There’s also a feature in Depence that meant I could control the lighting trusses and make some crazy positions out of them that I wouldn’t have been able to think of in my head, so that made a massive difference. The time I saved thinking of kinesis positions, meant I could spend more time programming.

What problems did you encounter and how did you solve them?

We did a lot of work in previz, but I also have a bit of knowledge about how kinesis works, so we didn’t actually run into too many problems. I guess one thing I can think of is that the kinesis motors have a minimum speed, so for some of the moves I wanted to do, the distance was too small over the allotted time I wanted to do it in, so we had to decide whether to let individual motors finish early, or just make the whole thing move faster depending on what was the best look for the show.

The final collaborative sessions tend to focus on removing things rather than adding them. We use visualisation software that can play back the show in real time – we can observe all the elements and how they interact with each other. It’s vital that the overall performance gives each element space to breathe. One of the main benefits of our approach is that all of the programming converges in house. It’s only natural that when each department is working individually that they think of the show with their element as the primary focus. This process, along with the fresh eyes of an overall show director, helps to look at the performance holistically as a durational experience, rather than as a series of individual moments. This was especially important given the kinetic elements which would affect lighting positions and block parts of the screen.

This is what commonly gets referred to as pre-visualisation, or previz. It’s also a time that the artist can come and observe the show virtually and feed back into the process before we get into physical rehearsals.

The final collaborative sessions tend to focus on removing things rather than adding them. We use visualisation software that can play back the show in real time – we can observe all the elements and how they interact with each other. It’s vital that the overall performance gives each element space to breathe. One of the main benefits of our approach is that all of the programming converges in house. It’s only natural that when each department is working individually that they think of the show with their element as the primary focus. This process, along with the fresh eyes of an overall show director, helps to look at the performance holistically as a durational experience, rather than as a series of individual moments. This was especially important given the kinetic elements which would affect lighting positions and block parts of the screen.

This is what commonly gets referred to as pre-visualisation, or previz. It’s also a time that the artist can come and observe the show virtually and feed back into the process before we get into physical rehearsals.

Concurrently to this creative process, the production team were busy planning the physical rehearsals alongside the debut performances of the show, which would all take place in the same week.

For Steve

Can you explain what this role of producer actually entails (sitting in between artist, management, agent, promoter, vendors, and venue)

What was the process of planning rehearsals and the brixton show?

What were the biggest challenges and how did you solve them?

We needed to find a dynamic and quickly editable way of hiding parts of the screen when the lighting trusses changed position and blocked off parts of the LED. It became clear that this was going to be a key structural issue, as if there was still media on the screen behind the lowered lighting, it would affect the audience’s ability to buy into these set changes as it would reveal all the cabling and metal work that we would prefer to keep hidden. To achieve this, we built an interactive video effect which got applied to the visuals as they were triggered. This program created a shape that would essentially mask the content inside it and could be controlled from the lighting desk. This meant the as the lighting trusses would physically transition from one position to another, this mask would also transition simultaneously, to keep the screen masked inside the trusses. We would also be able to control the position of the visuals themselves, so we could raise or lower the central point of any piece of visual content in realtime to match where the centre of the mask screen was in any of our different lighting states.